What Affected African Americansã¢â‚¬â„¢ Rights to Vote in the South During the Gilded Age?

*The American Yawp is an evolving, collaborative text. Please click here to amend this chapter.*

- I. Introduction

- Two. Industrialization & Technological Innovation

- Three. Clearing and Urbanization

- IV. The New South and the Problem of Race

- Five. Gender, Religion, and Culture

- VI. Conclusion

- VII. Primary Sources

- Viii. Reference Cloth

I. Introduction

When British author Rudyard Kipling visited Chicago in 1889, he described a city captivated by technology and blinded by greed. He described a rushed and crowded city, a "huge wilderness" with "scores of miles of these terrible streets" and their "hundred thousand of these terrible people." "The show impressed me with a great horror," he wrote. "There was no color in the street and no beauty—only a maze of wire ropes overhead and dingy rock flagging nether human foot." He took a cab "and the cabman said that these things were the proof of progress." Kipling visited a "gilded and mirrored" hotel "crammed with people talking about money, and spitting well-nigh everywhere." He visited extravagant churches and spoke with their congregants. "I listened to people who said that the mere fact of spiking down strips of iron to wood, and getting a steam and iron matter to run along them was progress, that the telephone was progress, and the network of wires overhead was progress. They repeated their statements once again and again." Kipling said American newspapers report "that the snarling together of telegraph-wires, the heaving up of houses, and the making of coin is progress."i

Wabash Avenue, Chicago, c. 1907. Library of Congress, LC-D4-70163.

Chicago embodied the triumph of American industrialization. Its meatpacking manufacture typified the sweeping changes occurring in American life. The last decades of the nineteenth century, a new era for big business, saw the formation of large corporations, run past trained bureaucrats and salaried managers, doing national and international business. Chicago, for instance, became America's butcher. The Chicago meat processing industry, a cartel of five firms, produced four fifths of the meat bought by American consumers. Kipling described in intimate item the Union Stock Yards, the nation'southward largest meat processing zone, a foursquare mile just southwest of the city whose pens and slaughterhouses linked the city'due south vast agronomical hinterland to the nation'due south dinner tables. "Once having seen them," he ended, "you volition never forget the sight." Like other notable Chicago industries, such every bit agricultural machinery and steel production, the meatpacking industry was closely tied to urbanization and immigration. In 1850, Chicago had a population of about thirty yard. Twenty years later on, it had three hundred thousand. Null could stop the city's growth. The Smashing Chicago Fire leveled 3.5 square miles and left a third of its residents homeless in 1871, simply the city quickly recovered and resumed its spectacular growth. Past the turn of the twentieth century, the metropolis was home to one.7 one thousand thousand people.

Chicago's explosive growth reflected national trends. In 1870, a quarter of the nation's population lived in towns or cities with populations greater than 2,500. Past 1920, a bulk did. Simply if many who flocked to Chicago and other American cities came from rural America, many others emigrated from overseas. Mirroring national immigration patterns, Chicago'due south newcomers had at starting time come by and large from Deutschland, the British Isles, and Scandinavia, only, by 1890, Poles, Italians, Czechs, Hungarians, Lithuanians, and others from southern and eastern Europe fabricated upwards a majority of new immigrants. Chicago, like many other American industrial cities, was as well an immigrant urban center. In 1900, nearly 80 percent of Chicago's population was either foreign-born or the children of foreign-born immigrants.two

Kipling visited Chicago simply as new industrial modes of production revolutionized the United States. The rise of cities, the evolution of American immigration, the transformation of American labor, the further making of a mass culture, the cosmos of great concentrated wealth, the growth of vast city slums, the conquest of the Westward, the emergence of a centre grade, the problem of poverty, the triumph of big business, widening inequalities, battles between capital letter and labor, the last destruction of independent farming, breakthrough technologies, environmental destruction: industrialization created a new America.

2. Industrialization & Technological Innovation

The railroads created the first great concentrations of uppercase, spawned the first massive corporations, made the first of the vast fortunes that would define the Aureate Age, unleashed labor demands that united thousands of farmers and immigrants, and linked many towns and cities. National railroad mileage tripled in the xx years afterward the outbreak of the Ceremonious War, and tripled once again over the 4 decades that followed. Railroads impelled the creation of uniform fourth dimension zones across the country, gave industrialists access to remote markets, and opened the American Due west. Railroad companies were the nation's largest businesses. Their vast national operations demanded the creation of innovative new corporate system, avant-garde management techniques, and vast sums of capital letter. Their huge expenditures spurred countless industries and attracted droves of laborers. And as they crisscrossed the nation, they created a national market, a truly national economy, and, seemingly, a new national culture.3

The railroads were non natural creations. Their vast majuscule requirements required the utilize of incorporation, a legal innovation that protected shareholders from losses. Enormous amounts of regime back up followed. Federal, state, and local governments offered unrivaled handouts to create the national rail networks. Lincoln'due south Republican Party—which dominated government policy during the Civil War and Reconstruction—passed legislation granting vast subsidies. Hundreds of millions of acres of state and millions of dollars' worth of government bonds were freely given to build the great transcontinental railroads and the innumerable trunk lines that rapidly annihilated the vast geographic barriers that had so long sheltered American cities from one another.

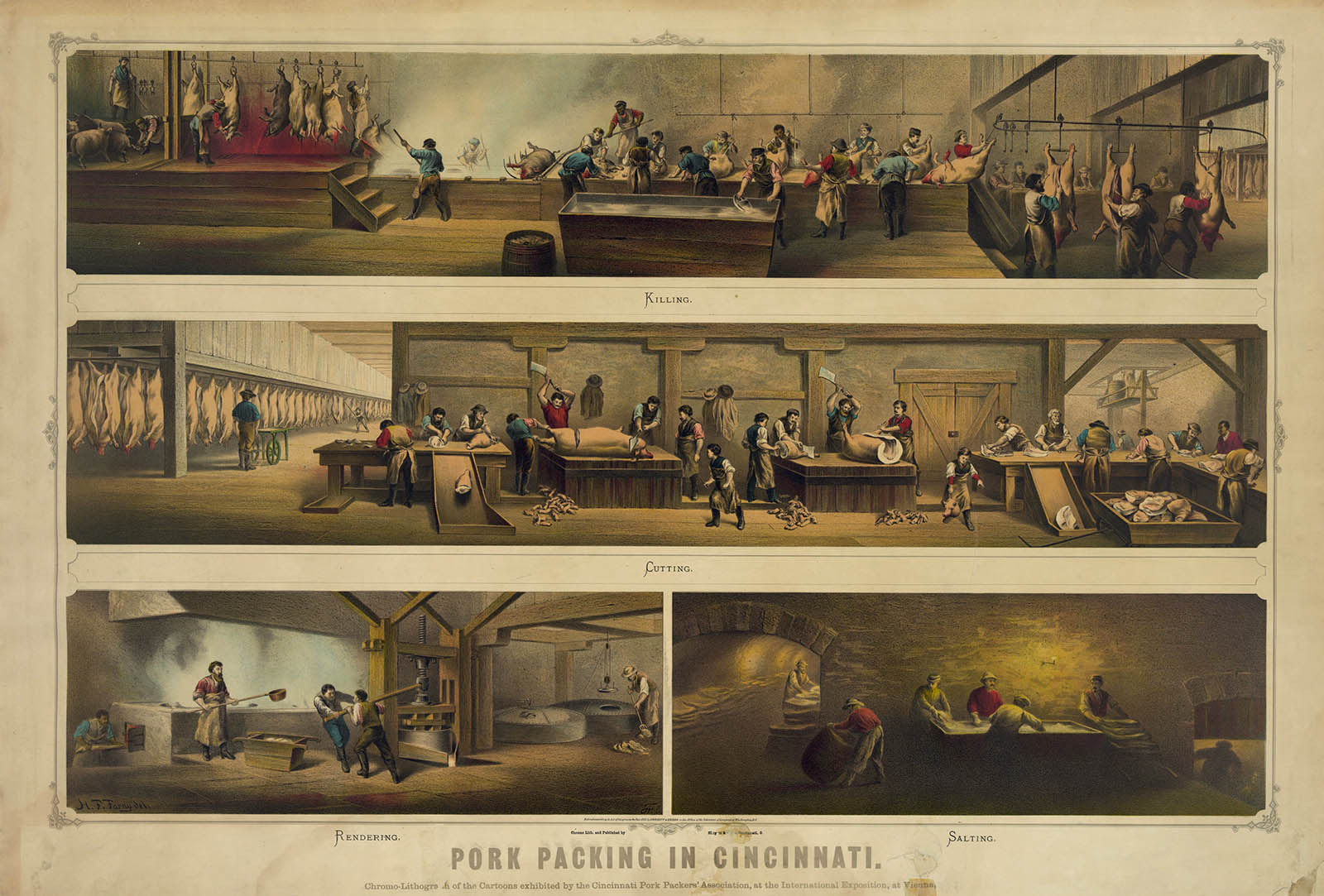

This impress shows the four stages of pork packing in nineteenth-century Cincinnati. This centralization of production made meat-packing an innovative industry, 1 of great interest to industrialists of all ilks. In fact, this chromo-lithograph was exhibited by the Cincinnati Pork Packers' Association at the International Exposition in Vienna, Austria. 1873. Wikimedia.

As railroad construction drove economic evolution, new means of production spawned new systems of labor. Many wage earners had traditionally seen factory work as a temporary stepping-stone to attaining their own modest businesses or farms. After the war, however, new technology and greater mechanization meant fewer and fewer workers could legitimately aspire to economical independence. Stronger and more organized labor unions formed to fight for a growing, more-permanent working class. At the same fourth dimension, the growing scale of economic enterprises increasingly disconnected owners from their employees and day-to-day business operations. To handle their vast new operations, owners turned to managers. Educated bureaucrats swelled the ranks of an emerging middle course.

Industrialization also remade much of American life outside the workplace. Rapidly growing industrialized cities knit together urban consumers and rural producers into a single, integrated national market. Food production and consumption, for case, were utterly nationalized. Chicago's stockyards seemingly tied it all together. Betwixt 1866 and 1886, ranchers drove a million caput of cattle annually overland from Texas ranches to railroad depots in Kansas for shipment by rail to Chicago. After travelling through modern "disassembly lines," the animals left the adjoining slaughterhouses equally slabs of meat to be packed into refrigerated rails cars and sent to butcher shops across the continent. By 1885, a handful of large-calibration industrial meatpackers in Chicago were producing nearly 5 hundred million pounds of "dressed" beef annually.4 The new scale of industrialized meat production transformed the landscape. Buffalo herds, grasslands, and old-growth forests gave fashion to cattle, corn, and wheat. Chicago became the Gateway Urban center, a crossroads connecting American agronomical goods, capital markets in New York and London, and consumers from all corners of the U.s.a..

Technological innovation accompanied economical development. For Apr Fool's Day in 1878, the New York Daily Graphic published a fictitious interview with the historic inventor Thomas A. Edison. The piece described the "biggest invention of the age"—a new Edison machine that could create xl different kinds of food and drinkable out of only air, water, and dirt. "Meat will no longer be killed and vegetables no longer grown, except by savages," Edison promised. The motorcar would end "famine and pauperism." And all for $five or $6 per machine! The story was a joke, of course, but Edison still received inquiries from readers wondering when the food machine would be prepare for the market. Americans had patently witnessed such startling technological advances—advances that would have seemed far-fetched mere years earlier—that the Edison food motorcar seemed entirely plausible.5

In September 1878, Edison appear a new and ambitious line of research and development—electric ability and lighting. The scientific principles backside dynamos and electric motors—the conversion of mechanical energy to electrical ability, and vice versa—were long known, just Edison practical the age's bureaucratic and commercial ethos to the problem. Far from a lonely inventor gripped by inspiration toiling in isolation, Edison advanced the model of commercially minded management of research and development. Edison folded his ii identities, business managing director and inventor, together. He called his Menlo Park research laboratory an "invention factory" and promised to turn out "a minor invention every x days and a big affair every six months or so." He brought his fully equipped Menlo Park enquiry laboratory and the skilled machinists and scientists he employed to touch on the problem of building an electric ability organisation—and commercializing it.

By belatedly fall 1879, Edison exhibited his arrangement of power generation and electrical light for reporters and investors. So he scaled up production. He sold generators to businesses. By the middle of 1883, Edison had overseen construction of 330 plants powering over lx thousand lamps in factories, offices, printing houses, hotels, and theaters around the world. He convinced municipal officials to build central power stations and run power lines. New York's Pearl Street central station opened in September 1882 and powered a square mile of downtown Manhattan. Electricity revolutionized the earth. It non only illuminated the nighttime, information technology powered the Second Industrial Revolution. Factories could operate anywhere at any hour. Electric rail cars allowed for cities to build out and electric elevators allowed for them to build up.

Economic advances, technological innovation, social and cultural evolution, demographic changes: the United states was a nation transformed. Manufacture boosted productivity, railroads connected the nation, more and more Americans labored for wages, new bureaucratic occupations created a vast "white collar" middle course, and unprecedented fortunes rewarded the owners of capital. These revolutionary changes, of course, would not occur without conflict or event (see Chapter 16), but they demonstrated the profound transformations remaking the nation. Alter was non bars to economics lone. Alter gripped the lives of everyday Americans and fundamentally reshaped American civilization.6

III. Clearing and Urbanization

State Street, due south from Lake Street, Chicago, Ill, ca.1900-1910. Library of Congress, LC-D4-70158.

Industry pulled ever more Americans into cities. Manufacturing needed the labor pool and the infrastructure. America's urban population increased sevenfold in the half century after the Civil State of war. Shortly the United States had more large cities than whatever country in the world. The 1920 U.Southward. census revealed that, for the showtime time, a majority of Americans lived in urban areas. Much of that urban growth came from the millions of immigrants pouring into the nation. Between 1870 and 1920, over twenty-five million immigrants arrived in the Us.

By the turn of the twentieth century, new immigrant groups such as Italians, Poles, and Eastern European Jews made upward a larger percent of arrivals than the Irish and Germans. The specific reasons that immigrants left their particular countries and the reasons they came to the U.s.a. (what historians call button and pull factors) varied. For instance, a young married man and married woman living in Sweden in the 1880s and unable to purchase farmland might read an ad for inexpensive land in the American Midwest and immigrate to the United States to begin a new life. A immature Italian man might simply hope to labor in a steel manufacturing plant long enough to relieve upward enough money to return home and purchase land for a family unit. A Russian Jewish family unit persecuted in European pogroms might expect to the United States as a sanctuary. Or perhaps a Japanese migrant might hear of fertile farming land on the Westward Coast and choose to canvas for California. But if many factors pushed people away from their habitation countries, by far the most important cistron cartoon immigrants was economics. Immigrants came to the U.s. looking for work.

Industrial commercialism was the nigh of import factor that drew immigrants to the U.s. betwixt 1880 and 1920. Immigrant workers labored in big industrial complexes producing goods such equally steel, textiles, and food products, replacing smaller and more local workshops. The influx of immigrants, alongside a large movement of Americans from the countryside to the urban center, helped propel the rapid growth of cities like New York, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Milwaukee, and St. Louis. Past 1890, immigrants and their children accounted for roughly sixty percent of the population in well-nigh large northern cities (and sometimes every bit high as 80 or 90 percent). Many immigrants, especially from Italian republic and the Balkans, always intended to return abode with enough money to purchase land. But what about those who stayed? Did the new arrivals digest together in the American melting pot—becoming just like those already in the United States—or did they retain, and sometimes even strengthen, their traditional ethnic identities? The answer lies somewhere in between. Immigrants from specific countries—and often even specific communities—often clustered together in indigenous neighborhoods. They formed vibrant organizations and societies, such equally Italian workmen'south clubs, Eastern European Jewish mutual assist societies, and Polish Cosmic churches, to ease the transition to their new American dwelling house. Immigrant communities published newspapers in dozens of languages and purchased spaces to proceed their arts, languages, and traditions alive. And from these foundations they facilitated even more than immigration: afterward staking out a claim to some corner of American life, they wrote habitation and encouraged others to follow them (historians telephone call this chain migration).

Many cities' politics adjusted to immigrant populations. The infamous urban political machines often operated every bit a kind of mutual assist lodge. New York City's Democratic Party machine, popularly known every bit Tammany Hall, drew the greatest ire from critics and seemed to embody all of the worst of city machines, but information technology as well responded to immigrant needs. In 1903, journalist William Riordon published a book, Plunkitt of Tammany Hall, which chronicled the activities of ward heeler George Washington Plunkitt. Plunkitt elaborately explained to Riordon the difference between "honest graft" and "dishonest graft": "I fabricated my pile in politics, but, at the same time, I served the system and got more big improvements for New York City than whatsoever other livin' human being." While exposing corruption, Riordon as well revealed the hard piece of work Plunkitt undertook on behalf of his largely immigrant constituency. On a typical day, Riordon wrote, Plunkitt was awakened at two a.m. to bail out a saloonkeeper who stayed open up likewise belatedly, was awakened over again at 6 a.grand. because of a fire in the neighborhood and spent time finding lodgings for the families displaced by the fire, and, afterwards spending the residual of the morning in courtroom to secure the release of several of his constituents, found jobs for four unemployed men, attended an Italian funeral, visited a church social, and dropped in on a Jewish nuptials. He returned abode at midnight.7

Tammany Hall's corruption, peculiarly under the reign of William "Dominate" Tweed, was legendary, but the public works projects that funded Tammany Hall'due south graft also provided essential infrastructure and public services for the city'southward rapidly expanding population. Water, sewer, and gas lines; schools, hospitals, civic buildings, and museums; law and fire departments; roads, parks (notably Central Park), and bridges (notably the Brooklyn Span): all could, in whole or in function, exist credited to Tammany's reign. Still, machine politics could never exist enough. Every bit the urban population exploded, many immigrants found themselves trapped in crowded, crime-ridden slums. Americans somewhen took observe of this urban crunch and proposed municipal reforms just also grew concerned near the declining quality of life in rural areas.

While cities boomed, rural worlds languished. Some Americans scoffed at rural backwardness and reveled in the countryside's decay, only many romanticized the countryside, celebrated rural life, and wondered what had been lost in the cities. Sociologist Kenyon Butterfield, concerned by the sprawling nature of industrial cities and suburbs, regretted the eroding social position of rural citizens and farmers: "Agriculture does not concord the same relative rank among our industries that information technology did in former years." Butterfield saw "the farm problem" as function of "the whole question of democratic civilization."8 He and many others idea the rise of the cities and the fall of the countryside threatened traditional American values. Many proposed conservation. Freedom Hyde Bailey, a botanist and rural scholar selected by Theodore Roosevelt to chair a federal Commission on Country Life in 1907, believed that rural places and industrial cities were linked: "Every agricultural question is a city question."9

Many longed for a eye path between the cities and the country. New suburban communities on the outskirts of American cities divers themselves in opposition to urban crowding. Americans contemplated the complicated relationships between rural places, suburban living, and urban spaces. Los Angeles became a model for the suburban evolution of rural places. Dana Barlett, a social reformer in Los Angeles, noted that the metropolis, stretching across dozens of small-scale towns, was "a ameliorate city" considering of its residential identity as a "city of homes."10 This linguistic communication was seized upon by many suburbs that hoped to avert both urban sprawl and rural disuse. In Glendora, i of these small towns on the outskirts of Los Angeles, local leaders were "loath as anyone to see information technology become cosmopolitan." Instead, in order to take Glendora "abound forth the lines necessary to have it remain an enjoyable urban center of homes," they needed to "bestir ourselves to directly its growth" by encouraging non manufacture or agriculture simply residential development.11

Iv. The New South and the Trouble of Race

"At that place was a South of slavery and secession," Atlanta Constitution editor Henry Grady proclaimed in an 1886 speech in New York. "That South is dead."12 Grady captured the sentiment of many white southern business and political leaders who imagined a New South that could plough its back to the past by embracing industrialization and diversified agriculture. He promoted the region's economical possibilities and mutual time to come prosperity through an brotherhood of northern capital and southern labor. Grady and other New Due south boosters hoped to shape the region'due south economic system in the Northward'due south image. They wanted industry and they wanted infrastructure. But the past could not exist escaped. Economically and socially, the "New S" would still be much like the old.

The ambitions of Atlanta, seen in the construction of such m buildings equally the Kimball House Hotel, reflected the larger regional aspirations of the then-chosen New South. 1890. Wikimedia.

A "New Southward" seemed an obvious need. The Confederacy'southward failed insurrection wreaked havoc on the southern economy and crippled southern prestige. Property was destroyed. Lives were lost. Political power vanished. And four meg enslaved Americans—representing the wealth and power of the antebellum white South—threw off their chains and walked proudly forward into freedom.

Emancipation unsettled the southern social club. When Reconstruction regimes attempted to grant freedpeople full citizenship rights, anxious whites struck back. From their fear, anger, and resentment they lashed out, non only in organized terrorist organizations such equally the Ku Klux Klan simply in political corruption, economic exploitation, and violent intimidation. White southerners took dorsum command of country and local governments and used their reclaimed power to disenfranchise African Americans and pass "Jim Crow" laws segregating schools, transportation, employment, and diverse public and private facilities. The reestablishment of white supremacy after the "redemption" of the South from Reconstruction contradicted proclamations of a "New" South. Possibly null harked so forcefully back to the barbaric southern by than the wave of lynchings—the extralegal murder of individuals by vigilantes—that washed beyond the South after Reconstruction. Whether for actual crimes or fabricated crimes or for no crimes at all, white mobs murdered roughly 5 thousand African Americans between the 1880s and the 1950s.

Lynching was non just murder, it was a ritual rich with symbolism. Victims were not merely hanged, they were mutilated, burned alive, and shot. Lynchings could become carnivals, public spectacles attended by thousands of eager spectators. Rail lines ran special cars to conform the blitz of participants. Vendors sold appurtenances and keepsakes. Perpetrators posed for photos and collected mementos. And it was increasingly common. 1 notorious example occurred in Georgia in 1899. Accused of killing his white employer and raping the man's wife, Sam Hose was captured by a mob and taken to the boondocks of Newnan. Word of the impending lynching chop-chop spread, and specially chartered rider trains brought some 4 thousand visitors from Atlanta to witness the gruesome affair. Members of the mob tortured Hose for virtually an hour. They sliced off pieces of his body equally he screamed in agony. And so they poured a can of kerosene over his body and burned him live.13

At the barbaric height of southern lynching, in the last years of the nineteenth century, southerners lynched ii to 3 African Americans every calendar week. In general, lynchings were most frequent in the Cotton Chugalug of the Lower South, where southern Blackness people were most numerous and where the majority worked as tenant farmers and field hands on the cotton farms of white landowners. Usa of Mississippi and Georgia had the greatest number of recorded lynchings: from 1880 to 1930, Mississippi lynch mobs killed over five hundred African Americans; Georgia mobs murdered more than than iv hundred.

Throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a number of prominent southerners openly supported lynching, arguing that it was a necessary evil to punish Black rapists and deter others. In the belatedly 1890s, Georgia newspaper columnist and noted women'due south rights activist Rebecca Latimer Felton—who would after go the get-go woman to serve in the U.Southward. Senate—endorsed such extrajudicial killings. She said, "If it takes lynching to protect women'southward dearest possession from drunken, ravening beasts, then I say lynch a thousand a week."14 When opponents argued that lynching violated victims' constitutional rights, South Carolina governor Coleman Blease angrily responded, "Whenever the Constitution comes between me and the virtue of the white women of Due south Carolina, I say to hell with the Constitution."15

This photograph captures the lynching of Laura and Lawrence Nelson, a mother and son, on May 25, 1911, in Okemah, Oklahoma. In response to national attention, the local white newspaper in Okemah but wrote, "While the general sentiment is adverse to the method, it is generally idea that the negroes got what would take been due them nether due process of law." Wikimedia.

Blackness activists and white allies worked to outlaw lynching. Ida B. Wells, an African American adult female born in the terminal years of slavery and a pioneering anti-lynching advocate, lost three friends to a lynch mob in Memphis, Tennessee, in 1892. That year, Wells published Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases, a groundbreaking work that documented the Southward's lynching culture and exposed the myth of the Black rapist.sixteen The Tuskegee Institute and the NAACP both compiled and publicized lists of every reported lynching in the The states. In 1918, Representative Leonidas Dyer of Missouri introduced federal anti-lynching legislation that would take made local counties where lynchings took place legally liable for such killings. Throughout the early 1920s, the Dyer Neb was the subject of heated political debate, but, fiercely opposed past southern congressmen and unable to win enough northern champions, the proposed pecker was never enacted.

Lynching was not but the form of racial violence that survived Reconstruction. White political violence continued to follow African American political participation and labor arrangement, however severely circumscribed. When the Populist insurgency created new opportunities for blackness political activism, white Democrats responded with terror. In North Carolina, Populists and Republicans "fused" together and won stunning electoral gains in 1896. Shocked White Democrats formed "Scarlet Shirt" groups, paramilitary organizations dedicated to eradicating black political participation and restoring Democratic rule through violence and intimidation. Launching a self-described "white supremacy campaign" of violence and intimidation against blackness voters and officeholders during the 1898 state elections, the Red Shirts effectively took back state government. Merely municipal elections were not held that year in Wilmington, where Fusionists controlled metropolis government. Later manning armed barricades blocking black voters from entering the town to vote in the state elections, the Red Shirts drafted a "White Declaration of Independence" which declared "that that we will no longer be ruled and volition never once again be ruled, by men of African origin." 457 white Democrats signed the document. They likewise issued a twelve-hour ultimatum that editor of the city's black daily newspaper flee the city. The editor left, but it wasn't enough. Twelve hours afterward, hundreds of Red Shirts raided the city's arsenal and ransacked the newspaper office anyway. The mob swelled and turned on the city'southward black neighborhood, destroying homes and businesses and opening fire on any Black person they found. Dozens were killed and hundreds more fled the metropolis. The mob then forced the mayor, the city's aldermen, and the police force main, at gun point, to immediately resign. To ensure their gains, the Democrats rounded up prominent fusionists, placed them on railroad cars, and, under armed guard, sent them out of the land. The mob installed and swore in their own replacements. It was a full-blown coup.

Lynching and organized terror campaigns were only the violent worst of the South's racial earth. Bigotry in employment and housing and the legal segregation of public and private life also reflected the ascent of a new Jim Crow S. So-chosen Jim Crow laws legalized what custom had long dictated. Southern states and municipalities enforced racial segregation in public places and in private lives. Separate coach laws were some of the commencement such laws to announced, beginning in Tennessee in the 1880s. Shortly schools, stores, theaters, restaurants, bathrooms, and nearly every other office of public life were segregated. And then too were social lives. The sin of racial mixing, critics said, had to be heavily guarded against. Marriage laws regulated against interracial couples, and white men, ever anxious of relationships betwixt Black men and white women, passed miscegenation laws and justified lynching as an appropriate extralegal tool to police the racial divide.

In politics, de facto limitations of Black voting had suppressed Blackness voters since Reconstruction. Whites stuffed ballot boxes and intimidated Black voters with physical and economical threats. And and so, from roughly 1890 to 1908, southern states implemented de jure, or legal, disfranchisement. They passed laws requiring voters to laissez passer literacy tests (which could be judged arbitrarily) and pay poll taxes (which hit poor white and poor Black Americans alike), effectively denying Black men the franchise that was supposed to have been guaranteed by the Fifteenth Amendment. Those responsible for such laws posed as reformers and justified voting restrictions as for the public good, a way to make clean upwards politics by purging corrupt African Americans from the voting rolls.

With white supremacy secured, prominent white southerners looked outward for support. New South boosters hoped to confront post-Reconstruction uncertainties by rebuilding the S'due south economy and convincing the nation that the South could be more than than an economically backward, race-obsessed backwater. And as they did, they began to retell the history of the recent past. A kind of civic religion known as the "Lost Crusade" glorified the Confederacy and romanticized the Old South. White southerners looked forward while simultaneously harking back to a mythic imagined past inhabited past contented and loyal slaves, chivalrous and generous masters, chivalric and honorable men, and pure and faithful southern belles. Secession, they said, had little to do with the institution of slavery, and soldiers fought only for domicile and honor, not the continued ownership of human beings. The New South, and so, would be built physically with new technologies, new investments, and new industries, but undergirded by political and social custom.

Henry Grady might take declared the Confederate South dead, but its memory pervaded the thoughts and actions of white southerners. Lost Cause champions overtook the S. Women's groups, such as the United Daughters of the Confederacy, joined with Confederate veterans to preserve a pro-Confederate by. They built Amalgamated monuments and celebrated Confederate veterans on Memorial 24-hour interval. Across the South, towns erected statues of General Robert E. Lee and other Confederate figures. By the plow of the twentieth century, the idealized Lost Cause by was entrenched not only in the South but beyond the country. In 1905, for case, Northward Carolinian Thomas F. Dixon published a novel, The Clansman, which depicted the Ku Klux Klan as heroic defenders of the South against the corruption of African American and northern "carpetbag" misrule during Reconstruction. In 1915, acclaimed film managing director David Due west. Griffith adapted Dixon'south novel into the groundbreaking blockbuster film, Nativity of a Nation. (The film nearly singlehandedly rejuvenated the Ku Klux Klan.) The romanticized version of the antebellum South and the distorted version of Reconstruction dominated popular imagination.17

While Lost Cause defenders mythologized their past, New South boosters struggled to wrench the South into the modern globe. The railroads became their focus. The region had lagged behind the N in the railroad building nail of the midnineteenth century, and postwar expansion facilitated connections between the about rural segments of the population and the region's rising urban areas. Boosters campaigned for the construction of new difficult-surfaced roads as well, arguing that improved roads would farther increase the flow of appurtenances and people and entice northern businesses to relocate to the region. The ascent popularity of the automobile after the turn of the century merely increased pressure level for the construction of reliable roads between cities, towns, canton seats, and the vast farmlands of the S.

Along with new transportation networks, New South boosters continued to promote industrial growth. The region witnessed the rise of various manufacturing industries, predominantly textiles, tobacco, article of furniture, and steel. While agriculture—cotton in particular—remained the mainstay of the region's economy, these new industries provided new wealth for owners, new investments for the region, and new opportunities for the exploding number of landless farmers to finally flee the country. Industries offered low-paying jobs but also opportunity for rural poor who could no longer sustain themselves through subsistence farming. Men, women, and children all moved into wage work. At the turn of the twentieth century, almost one quaternary of southern mill workers were children anile six to xvi.

In almost cases, every bit in most aspects of life in the New Southward, new mill jobs were racially segregated. Better-paying jobs were reserved for whites, while the most unsafe, labor-intensive, dirtiest, and everyman-paying positions were relegated to African Americans. African American women, close out of nigh industries, found employment most oftentimes every bit domestic help for white families. Every bit poor as white southern manufactory workers were, southern Black people were poorer. Some white mill workers could even afford to pay for domestic help in caring for young children, cleaning houses, doing laundry, and cooking meals. Manufacturing plant villages that grew upwards aslope factories were whites-only, and African American families were pushed to the outer perimeter of the settlements.

That a "New South" emerged in the decades between Reconstruction and World War I is debatable. If measured past industrial output and railroad construction, the New Due south was a reality merely if measured relative to the rest of the nation, it was a limited i. If measured in terms of racial discrimination, however, the New South looked much like the One-time. Boosters such as Henry Grady said the Southward was done with racial questions just lynching and segregation and the institutionalization of Jim Crow exposed the South's lingering racial obsessions. Meanwhile, virtually southerners however toiled in agriculture and nonetheless lived in poverty. Industrial development and expanding infrastructure, rather than re-creating the Due south, coexisted easily with white supremacy and an impoverished agronomical economy. The trains came, factories were built, and upper-case letter was invested, merely the region remained mired in poverty and racial apartheid. Much of the "New South," then, was anything but new.

V. Gender, Organized religion, and Culture

Visitors to the Columbian Exposition of 1893 took in the view of the Court of Honor from the roof of the Manufacturers Building. Art Found of Chicago, via Wikimedia

In 1905, Standard Oil tycoon John D. Rockefeller donated $100,000 (about $2.five meg today) to the American Board of Commissioners for Strange Missions. Rockefeller was the richest man in America merely also one of the most hated and mistrusted. Even admirers conceded that he achieved his wealth through often illegal and commonly immoral business practices. Journalist Ida Tarbell had fabricated waves describing Standard Oil'southward long-standing ruthlessness and predilections for political corruption. Clergymen, led by reformer Washington Gladden, fiercely protested the donation. A decade earlier, Gladden had asked of such donations, "Is this clean money? Can any man, can whatever institution, knowing its origin, touch information technology without being defiled?" Gladden said, "In the cool brutality with which properties are wrecked, securities destroyed, and people past the hundreds robbed of their piffling all to build up the fortunes of the multi-millionaires, we have an appalling revelation of the kind of monster that a man existence may become."18

Despite widespread criticism, the lath accepted Rockefeller'southward donation. Board president Samuel Capen did not defend Rockefeller, arguing that the gift was charitable and the board could not appraise the origin of every donation, just the dispute shook Capen. Was a corporate groundwork incompatible with a religious organization? The "tainted coin debate" reflected questions about the proper relationship between religion and commercialism. With rising income inequality, would religious groups exist forced to back up either the elite or the disempowered? What was moral in the new industrial U.s.? And what obligations did wealth bring? Steel magnate Andrew Carnegie popularized the idea of a "gospel of wealth" in an 1889 article, claiming that "the true antidote for the temporary diff distribution of wealth" was the moral obligation of the rich to give to charity.nineteen Farmers and labor organizers, meanwhile, argued that God had blessed the weak and that new Gilded Age fortunes and corporate direction were inherently immoral. As time passed, American churches increasingly adapted themselves to the new industrial social club. Even Gladden came to accept donations from the and so-called robber barons, such every bit the Baptist John D. Rockefeller, who increasingly touted the morality of business. Meanwhile, every bit many churches wondered well-nigh the compatibility of large fortunes with Christian values, others were concerned for the fate of traditional American masculinity.

The economic and social changes of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries—including increased urbanization, immigration, advancements in science and technology, patterns of consumption and the new availability of goods, and new awareness of economic, racial, and gender inequalities—challenged traditional gender norms. At the same fourth dimension, urban spaces and shifting cultural and social values presented new opportunities to claiming traditional gender and sexual norms. Many women, carrying on a campaign that stretched long into the past, vied for equal rights. They became activists: they targeted municipal reforms, launched labor rights campaigns, and, above all, bolstered the suffrage movement.

Urbanization and immigration fueled anxieties that old social mores were being subverted and that onetime forms of social and moral policing were increasingly inadequate. The anonymity of urban spaces presented an opportunity in particular for female sexuality and for male and female sexual experimentation along a spectrum of orientations and gender identities. Anxiety over female person sexuality reflected generational tensions and differences, too as racial and class ones. Every bit young women pushed back confronting social mores through premarital sexual exploration and expression, social welfare experts and moral reformers labeled such girls feeble-minded, believing even that such unfeminine behavior could be symptomatic of clinical insanity rather than free-willed expression. Generational differences exacerbated the social and familial tensions provoked by shifting gender norms. Youths challenged the norms of their parents' generations past donning new fashions and enjoying the delights of the city. Women's way loosed its concrete constraints: corsets relaxed and hemlines rose. The newfound physical liberty enabled by looser dress was also mimicked in the pursuit of other freedoms.

While many women worked to liberate themselves, many, sometimes simultaneously, worked to uplift others. Women'south piece of work confronting alcohol propelled temperance into 1 of the foremost moral reforms of the catamenia. Middle-class, typically Protestant women based their assault on alcohol on the footing of their feminine virtue, Christian sentiment, and their protective role in the family unit and home. Others, like Jane Addams and settlement house workers, sought to impart a middle-grade education on immigrant and working-form women through the institution of settlement homes. Other reformers touted a "scientific motherhood": the new science of hygiene was deployed as a method of both social uplift and moralizing, specially of working-class and immigrant women.

Taken a few years after the publication of "The Yellow Wallpaper," this portrait photograph shows activist Charlotte Perkins Gilman's feminine poise and respectability even as she sought massive change for women's identify in society. An outspoken supporter of women'southward rights, Gilman's works challenged the supposedly "natural" inferiority of women. Wikimedia.

Women vocalized new discontents through literature. Charlotte Perkins Gilman's short story "The Yellow Wallpaper" attacked the "naturalness" of feminine domesticity and critiqued Victorian psychological remedies administered to women, such as the "rest cure." Kate Chopin'due south The Enkindling, set in the American South, as well criticized the domestic and familial role ascribed to women by club and gave expression to feelings of malaise, desperation, and desire. Such literature straight challenged the status quo of the Victorian era's constructions of femininity and feminine virtue, as well every bit established feminine roles.

While many men worried well-nigh female person activism, they worried too virtually their own masculinity. To broken-hearted observers, industrial capitalism was withering American manhood. Rather than working on farms and in factories, where young men formed physical muscle and spiritual dust, new generations of workers labored behind desks, wore white collars, and, in the words of Supreme Courtroom Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, appeared "black-coated, stiff-jointed, soft-muscled, [and] paste-complexioned."20 Neurologist George Beard fifty-fifty coined a medical term, neurasthenia, for a new emasculated condition that was marked by low, indigestion, hypochondria, and extreme nervousness. The philosopher William James chosen it "Americanitis." Academics increasingly warned that America had become a nation of emasculated men.

Churches too worried near feminization. Women had always comprised a articulate bulk of church memberships in the United States, but now the theologian Washington Gladden said, "A preponderance of female influence in the Church or anywhere else in social club is unnatural and injurious." Many feared that the feminized church had feminized Christ himself. Rather than a rough-hewn carpenter, Jesus had been made "mushy" and "sweetly effeminate," in the words of Walter Rauschenbusch. Advocates of a so-called muscular Christianity sought to stiffen young men'south backbones by putting them dorsum in bear on with their primal manliness. Pulling from contemporary developmental theory, they believed that young men ought to evolve as civilization evolved, advancing from primitive nature-dwelling to modern industrial enlightenment. To facilitate "primitive" encounters with nature, muscular Christians founded summer camps and outdoor boys' clubs similar the Woodcraft Indians, the Sons of Daniel Boone, and the Male child Brigades—all precursors of the Boy Scouts. Other champions of muscular Christianity, such every bit the newly formed Young Men's Christian Clan, congenital gymnasiums, often fastened to churches, where youths could strengthen their bodies as well as their spirits. It was a Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA) leader who coined the term bodybuilding, and others invented the sports of basketball game and volleyball.21

Muscular Christianity, though, was nearly even more than edifice strong bodies and minds. Many advocates as well ardently championed Western imperialism, cheering on attempts to civilize non-Western peoples. Gilded Age men were encouraged to embrace a item vision of masculinity continued intimately with the rising tides of nationalism, militarism, and imperialism. Contemporary ideals of American masculinity at the plough of the century developed in concert with the United States' regal and militaristic endeavors in the Westward and abroad. During the Castilian-American War in 1898, Teddy Roosevelt and his Crude Riders embodied the idealized paradigm of the tall, strong, virile, and fit American man that simultaneously epitomized the ideals of ability that informed the United States' imperial agenda. Roosevelt and others similar him believed a reinvigorated masculinity would preserve the American race'due south superiority against foreign foes and the effeminizing effects of overcivilization.

Amusement-hungry Americans flocked to new entertainments at the turn of the twentieth century. In this early on-twentieth-century photo, visitors savor Luna Park, i of the original amusement parks on Brooklyn's famous Coney Isle. Visitors to Coney Island'due south Luna Park, ca.1910-1915. Library of Congress (LC-B2- 2240-13).

But while many fretted nearly traditional American life, others lost themselves in new forms of mass culture. Vaudeville signaled new cultural worlds. A unique variety of popular entertainments, these traveling excursion shows first appeared during the Ceremonious War and peaked betwixt 1880 and 1920. Vaudeville shows featured comedians, musicians, actors, jugglers, and other talents that could captivate an audience. Unlike earlier rowdy acts meant for a male audience that included alcohol, vaudeville was considered family-friendly, "polite" entertainment, though the acts involved offensive ethnic and racial caricatures of African Americans and recent immigrants. Vaudeville performances were often small-scale and quirky, though venues such as the renowned Palace Theatre in New York City signaled true distinction for many performers. Popular entertainers such equally silent flick star Charlie Chaplin and magician Harry Houdini made names for themselves on the vaudeville excursion. Merely if alive entertainment still captivated audiences, others looked to entirely new technologies.

Past the plough of the century, two technologies pioneered by Edison—the phonograph and motion pictures—stood ready to revolutionize leisure and assist create the mass entertainment culture of the twentieth century. The phonograph was the get-go reliable device capable of recording and reproducing sound. But information technology was more than than that. The phonograph could create multiple copies of recordings, sparking a great expansion of the market for pop music. Although the phonograph was a technical success, Edison at starting time had trouble developing commercial applications for it. He thought it might be used for dictation, recording audio letters, preserving speeches and dying words of great men, producing talking clocks, or teaching elocution. He did not anticipate that its greatest use would be in the field of mass amusement, only Edison'due south sales agents soon reported that many phonographs were being used for only that, especially in so-called phonograph parlors, where customers could pay a nickel to hear a piece of music. By the plow of the century, Americans were purchasing phonographs for dwelling use. Amusement became the phonograph'south major market.

Inspired by the success of the phonograph as an entertainment device, Edison decided in 1888 to develop "an instrument which does for the Centre what the phonograph does for the Ear." In 1888, he patented the concept of motility pictures. In 1889, he innovated the rolling of film. By 1891, he was exhibiting a motion-picture camera (a kinetograph) and a viewer (a kinetoscope). By 1894, the Edison Company had produced nearly seventy-five films suitable for sale and viewing. They could exist viewed through a small eyepiece in an arcade or parlor. They were short, typically about iii minutes long. Many of the early on films depicted athletic feats and competitions. I 1894 picture show, for example, showed a 6-round boxing lucifer. The itemize description gave a sense of the appeal it had for male viewers: "Full of hard fighting, clever hits, punches, leads, dodges, body blows and some slugging." Other early kinetoscope subjects included Indian dances, nature and outdoor scenes, re-creations of historical events, and humorous skits. Past 1896, the Edison Vitascope could project film, shifting audiences abroad from arcades and pulling them into theaters. Edison's motion picture itemize meanwhile grew in sophistication. He sent filmmakers to distant and exotic locales like Japan and China. Long-form fictional films created a need for "moving picture stars," such as the glamorous Mary Pickford, the swashbuckling Douglas Fairbanks, the acrobatic comedian Buster Keaton, who began to appear in the popular imagination beginning around 1910. Alongside professional boxing and baseball, the picture industry was creating the modern culture of glory that would narrate twentieth-century mass entertainment.22

VI. Determination

Designers of the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago built the White City in a neoclassical architectural manner. The integrated blueprint of buildings, walkways, and landscapes propelled the burgeoning City Cute movement. The Fair itself was a huge success, bringing more than twenty-7 million people to Chicago and helping to establish the ideology of American exceptionalism. Wikimedia.

After enduring four bloody years of warfare and a strained, decade-long effort to reconstruct the defeated South, the United States abandoned itself to industrial development. Businesses expanded in calibration and telescopic. The nature of labor shifted. A heart form rose. Wealth concentrated. Immigrants crowded into the cities, which grew upward and outward. The Jim Crow South stripped away the vestiges of Reconstruction, and New South boosters papered over the scars. Industrialists hunted profits. Evangelists appealed to people'southward morals. Consumers lost themselves in new goods and new technologies. Women emerging into new urban spaces embraced new social possibilities. In all of its many facets, by the turn of the twentieth century, the United States had been radically transformed. And the transformations connected to ripple outward into the West and overseas, and in into radical protest and progressive reforms. For Americans at the twilight of the nineteenth century and the dawn of the twentieth, a bold new world loomed.

VII. Main Sources

1. Andrew Carnegie on "The Triumph of America" (1885)

Steel magnate Andrew Carnegie celebrated and explored American economic progress in this 1885 article, afterwards reprinted in his 1886 book,Triumphant Democracy.

2. Henry Grady on the New South (1886)

Atlanta newspaperman and campaigner of the "New South," Henry Grady, won national recognition for his December 21, 1886 speech to the New England Lodge in New York City.

3. Ida B. Wells-Barnett, "Lynch Law in America" (1900)

Ida B. Wells-Barnett, born enslaved in Mississippi, was a pioneering activist and journalist. She did much to betrayal the epidemic of lynching in the United States and her writing and research exploded many of the justifications—particularly the rape of white women by Black men—commonly offered to justify the practise.

4. Henry Adams,The Instruction of Henry Adams (1918)

Henry Adams, the great grandson of President John Adams, the grandson of President John Quincy Adams, the son of a major American diplomat, and an achieved Harvard historian, writing in the third person, describes his feel at the Great Exposition in Paris in 1900 and writes of his encounter with "forces totally new."

five. Charlotte Perkins Gilman, "Why I WroteThe Yellow Wallpaper" (1913)

Charlotte Perkins Gilman won much attending in 1892 for publishing "The Xanthous Wallpaper," a semi-autobiographical short story dealing with mental health and contemporary social expectations for women. In the following piece, Gilman reflected on writing and publishing the piece.

6. Jacob Riis,How the Other Half Lives (1890)

Jacob Riis, a Danish immigrant, combined photography and journalism into a powerful indictment of poverty in America. His 1890,How the Other Half Livesshocked Americans with its raw depictions of urban slums. Here, he describes poverty in New York.

7. Rose Cohen on the Earth Beyond her Immigrant Neighborhood (ca.1897/1918)

Rose Cohen was born in Russia in 1880 as Rahel Golub. She immigrated to the United states in 1892 and lived in a Russian Jewish neighborhood in New York's Lower East Side. Her, she writes about her run across with the world exterior of her ethnic neighborhood.

8. Mulberry Street (ca. 1900)

At the plough of the century, New York Urban center's Lower E Side became the well-nigh densely packed urban surface area in the earth. This colorized photomechanical print from the Detroit Photographic depicts daily life on Mulberry Street, the surface area's central avenue.

9. Coney Island (ca. 1910-1915)

Amusement-hungry Americans flocked to new entertainments at the turn of the twentieth century. In this early-twentieth century photograph, visitors relish Luna Park, one of the original entertainment parks on Brooklyn's famous Coney Island.

Viii. Reference Fabric

This affiliate was edited past David Hochfelder, with content contributions by Jacob Betz, David Hochfelder, Gerard Koeppel, Scott Libson, Kyle Livie, Paul Matzko, Isabella Morales, Andrew Robichaud, Kate Sohasky, Joseph Super, Susan Thomas, Kaylynn Washnock, and Kevin Immature.

Recommended citation: Jacob Betz et al., "Life in Industrial America," David Hochfelder, ed., in The American Yawp, eds. Joseph Locke and Ben Wright (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2018).

Recommended Reading

- Ayers, Edward. The Promise of the New South. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

- Beckert, Sven. Monied Urban center: New York City and the Consolidation of the American Bourgeoisie, 1850–1896. Cambridge, Great britain: Cambridge Academy Press, 2001.

- Bederman, Gail. Manliness and Civilization: A Cultural History of Gender and Race in the Usa, 1880–1917. Chicago: Academy of Chicago Press, 1995.

- Bane, David. Race and Reunion: The Civil State of war in American Memory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001.

- Briggs, Laura. "The Race of Hysteria: 'Overcivilization' and the 'Savage' Woman in Late Nineteenth-Century Obstetrics and Gynecology." American Quarterly 52 (June 2000). 246–273.

- Chauncey, George. Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890–1940. New York: Bones Books, 1995.

- Cole, Stephanie, and Natalie J. Ring, eds. The Folly of Jim Crow: Rethinking the Segregated South. College Station: Texas A&Thousand University Press, 2012.

- Cott, Nancy. The Grounding of Mod Feminism. New Oasis, CT: Yale Academy Press, 1987.

- Cronon, William. Nature'southward Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West. New York: Norton, 1991.

- Edwards, Rebecca. New Spirits: Americans in the Gilded Age, 1865–1905. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Gilmore, Glenda Elizabeth. Gender and Jim Crow: Women and the Politics of White Supremacy in North Carolina, 1896–1920. Chapel Colina: Academy of North Carolina Press, 1996.

- Gutman, Herbert. Work, Civilization and Social club in Industrializing America: Essays in American Working-Grade and Social History. New York: Knopf, 1976.

- Hale, Grace Elizabeth. Making Whiteness: The Civilization of Segregation in the South, 1890–1940. New York: Pantheon Books, 1998.

- Hicks, Cheryl. Talk with You Like a Woman: African American Women, Justice, and Reform in New York, 1890–1935. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Printing, 2010.

- Kasson, John F. Agreeable the Million: Coney Island at the Turn of the Century. New York: Hill and Wang, 1978.

- Leach, William. Land of Desire: Merchants, Power, and the Rise of a New American Culture. New York: Random Business firm, 1993.

- Lears, T. J. Jackson. No Identify of Grace: Antimodernism and the Transformation of American Culture, 1880–1920. Chicago: Academy of Chicago Press, 1981.

- Odem, Mary. Delinquent Daughters: Protecting and Policing Adolescent Female Sexuality in the United States, 1885–1920. Chapel Hill: University of N Carolina Press, 1995.

- Peiss, Kathy. Inexpensive Amusements. Working Women and Leisure in Turn-of-the-Century New York. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1986.

- Peiss, Kathy. Hope in a Jar: The Making of America's Beauty Culture. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999.

- Putney, Clifford. Manhood and Sports in Protestant America, 1880–1920. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001.

- Silber, Nina. The Romance of Reunion: Northerners and the South, 1865–1900. Chapel Hill: Academy of Due north Carolina Printing, 1997.

- Strouse, Jean. Alice James: A Biography. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1980.

- Trachtenberg, Alan. The Incorporation of America: Civilisation and Society in the Gold Age. New York: Loma and Wang, 2007.

- Woodward, C. Vann. Origins of the New Due south, 1877–1913. Baton Rouge: LSU Printing, 1951.

Notes

Source: http://www.americanyawp.com/text/18-industrial-america/

Post a Comment for "What Affected African Americansã¢â‚¬â„¢ Rights to Vote in the South During the Gilded Age?"